Have you ever felt like your appetite has a mind of its own? One day you’re perfectly satisfied with a normal meal, and the next you’re rummaging through the pantry an hour after eating. This isn’t just about cravings or willpower—it’s biology. Your body is guided by a finely tuned hormonal system that controls when you feel hungry, how full you feel after eating, and even what foods you crave. These are your hunger hormones, and when they’re in balance, eating feels natural and intuitive. But when they’re out of sync, everything from portion control to food choices can become a struggle.

Meet the Two Major Players: Ghrelin and Leptin

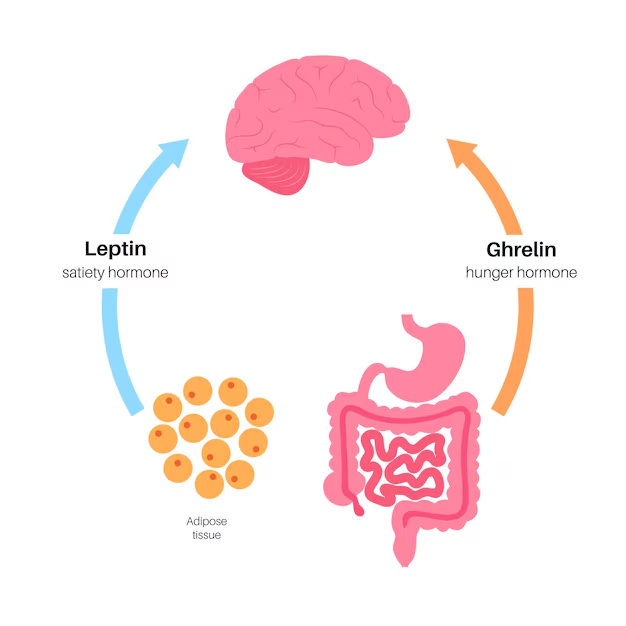

The two most important hunger-related hormones are ghrelin and leptin. These work together in a feedback loop to keep your appetite and energy stores in balance.

Ghrelin, often called the “hunger hormone,” is produced primarily in the stomach and released when your body senses that it’s time to refuel. It rises before meals and falls after eating, sending a clear signal to your brain: “It’s time to eat.”When functioning properly, this feedback loop helps regulate your eating patterns throughout the day. However, factors like sleep deprivation, chronic dieting, and stress can increase ghrelin production, making you feel hungrier than your body actually needs to be.

On the opposite side is leptin, produced by your fat cells. Leptin’s job is to signal the brain that you’ve eaten enough and have sufficient stored energy. The more fat you have, the more leptin your body produces. But in cases of excess weight or obesity, the brain can become resistant to leptin—a condition known as leptin resistance. This means that even with high leptin levels, your brain still perceives starvation, leading to persistent hunger and slower metabolism.

The Supporting Cast: More Hormones That Influence Hunger

While ghrelin and leptin get most of the attention, they don’t act alone. Several other hormones quietly influence your appetite and fullness in important ways:

Insulin

Produced by the pancreas, insulin helps move glucose (sugar) into your cells for energy and also plays a role in satiety. After eating, insulin levels rise to help manage blood sugar. However, diets high in refined carbs can lead to chronically elevated insulin, contributing to insulin resistance. This not only disrupts blood sugar balance but also impairs satiety signaling, making you feel hungry even when your body doesn’t need more food.

Cortisol

Known as the body’s main stress hormone, cortisol is essential in small bursts but problematic when chronically elevated. Ongoing stress can keep cortisol levels high, which has been shown to increase cravings—especially for high-fat, high-sugar comfort foods. It can also contribute to abdominal fat and worsen insulin resistance.

Peptide YY (PYY)

Released in the small intestine after you eat, PYY helps reduce appetite by slowing down gut motility and enhancing the feeling of fullness. Protein-rich meals are especially effective at stimulating PYY. Low levels of this hormone may be associated with increased appetite and overeating.

Cholecystokinin (CCK)

Also produced in the small intestine, CCK is released when you consume fats and proteins. It slows digestion and signals satiety to the brain, helping you feel full sooner and stay full longer. Like PYY, CCK supports portion control by naturally encouraging smaller meal sizes.

GLP-1 (Glucagon-Like Peptide-1)

GLP-1 is another gut hormone released after eating, particularly in response to carbohydrate and fat intake. It stimulates insulin production, slows gastric emptying, and promotes a feeling of satiety. GLP-1 is also the target of popular medications used to support weight loss and type 2 diabetes management because of its appetite-suppressing effects.

When Your Hunger Hormones Are Out of Sync

When these hormones are disrupted—by poor sleep, stress, irregular eating patterns, or extreme diets—the body’s internal hunger cues can become distorted. You might feel hungry when your body doesn’t need food, or fail to feel full even after eating enough. Over time, ignoring these cues can contribute to weight gain, low energy, mood swings, and a dysfunctional relationship with food. Hormonal imbalances can also cause people to eat out of habit, emotion, or impulse rather than true hunger.

How to Rebalance and Support Your Hunger Hormones

The good news is that simple lifestyle choices can help restore balance and improve how these hormones function.

Prioritize quality sleep, aiming for 7–9 hours per night. Even one night of poor sleep can increase ghrelin and decrease leptin, making it harder to manage hunger the next day.

Eat regular, balanced meals that include protein, fiber, and healthy fats—these macronutrients help stimulate PYY, CCK, and GLP-1 while regulating ghrelin and insulin.

Stress management is another critical factor. Chronic stress elevates cortisol and can drive emotional or impulsive eating. Daily stress-reduction practices like walking, breathwork, mindfulness, or yoga can make a meaningful difference.

Physical activity, even light movement after meals, can improve insulin sensitivity and help your body respond better to leptin.

Lastly, stay hydrated. Thirst is often mistaken for hunger, and drinking enough water can help keep appetite signals clearer.

Tuning Into Your Body’s Signals

Ultimately, the goal isn’t to suppress hunger—it’s to understand and respond to it in a healthy way. Your hunger hormones are messengers, not enemies. When you work with them rather than against them, eating becomes more intuitive, satisfying, and sustainable.

By learning to respect your body’s signals, support hormone balance through lifestyle, and let go of diet extremes, you can build a healthier relationship with food—and with yourself.